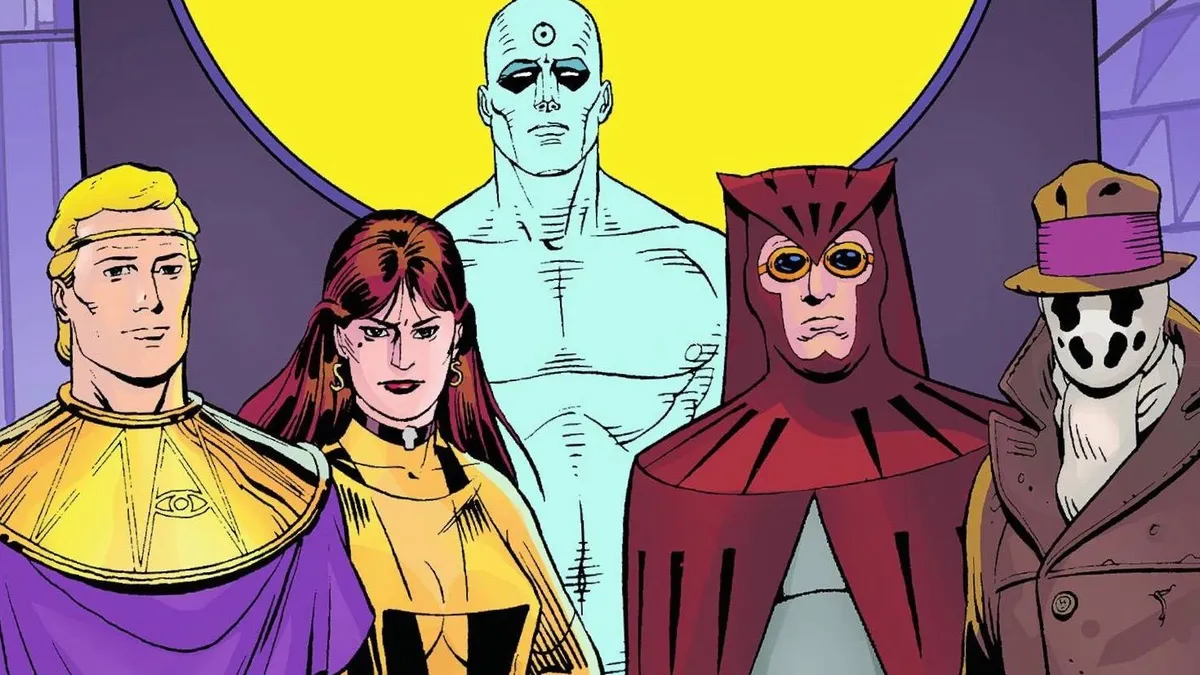

The acclaim surrounding Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen is unparalleled in the graphic novel world. It is the only graphic novel to win the annual Hugo Award for best science fiction or fantasy work of the previous year, and the only graphic novel named to Time Magazine’s “All-Time 100 Novels” list alongside some classics that can be found in the East Islip High School bookroom such as The Great Gatsby, To Kill a Mockingbird, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

The first time I read Watchmen was ten years ago. It was my first year teaching and a student recommended it and later gave me his personal copy to keep. It meant so much to me then and its even more special because I can share the experience with another student a decade later. I’m excited to be there to hear about Jack’s reaction to what is arguably the best graphic novel ever written.

MA: I hope Jack appreciates the level of sophistication of the storyline – Moore somehow finds the time to fully characterize 7-10 extremely complex characters, while also creating a history of two generations of “masked adventurers” and capturing a society and political climate that is on the brink of World War III. For the most part, the story is told in the style of comics, but each chapter contains a unique element that helps add depth and background to characters that is specifically NOT in the comic style. These include several chapters from a character’s “tell-all” autobiography, articles from different magazines that represent two very different political voices, and even the medical reports from the character Rorschach’s psychological evaluations.

There’s so much I can identify specifically that I want to discuss with Jack, but to narrow it down, my favorite sequences are those that explain the idea that Dr. Manhattan experiences all of time at once. The chapter – “Watchmaker” – essentially gives Dr. Manhattan’s origin story, but tells it in the way he thinks. It is all told in the present tense: “it is 1945. I am sixteen years old” and just one panel later “it is 1985. I am fifty-six years old.” What makes this sequence so meaningful is that the world sees Dr. Manhattan as a larger than life superhero in the real world that not only becomes the ultimate defense for the United States, but also a celebrity. This section solidifies that no one understands Dr. Manhattan because no one CAN understand exactly the way he sees the world. Confusing, I know! But so interesting and definitely something that has to be read more than once. It’s worth it.

JW: As a fan of the superhero genre, and its creative thematic truths, I am shocked that I have not picked up Watchmen until Mr. Augello convinced me to. The graphic novel creates a breathing world within its pages, with each character displaying complex motives and forming into their own in reaction to the devastating events leading up to the death of the Comedian. These characters are specifically what jumped out to me, so much of what I have to say is centered around these “Watchmen”.

Ironically, Dr. Manhattan’s tale was the most gripping aspect of the graphic novel for me as well. I think most of the comic’s fans would agree. Dr. Manhattan’s inadvertent ability to experience time for what it truly is adds an interesting conflict to the story. In Moore and Gibbon’s gritty world, humanity is losing its grip with reality. The world has grown so far into madness, that the line between sanity and insanity has seemingly disappeared.

The reason why Dr. Manhattan’s perception of time plays into this is masterful. Dr. Manhattan is more than human, which causes him to view this world of humans as beneath him. After being turned into a living weapon by the United States, he loses touch with the value of life. His only connection to the human race is his love for Laurie, a fellow “masked adventurer,” but that does not stop him from abandoning them. He fears that his impact on their world is far too great for him to remain with them.

On Mars, Dr. Manhattan finds a home. He finds a place that finally allows him to grapple with his thoughts. As mentioned earlier, “Watchmaker” sees Dr. Manhattan playing through his memories as though they all exist in the present. It makes his memories feel insignificant on the dunes of Mars. And thus, Dr. Manhattan fully detaches himself from the predictability of humankind.

However, it is his love for Laurie that pulls him full circle. After a confrontation with Laurie on Mars, Laurie shows Dr. Manhattan just how worth saving humankind really is. Through the revelation of Laurie’s father, and her mother’s love for him, Dr. Manhattan rethinks his decision to abandon humanity and ends up saving them from Ozymandias.

As I was reading more about Ozymandias, I could not help but think of Rorschach, who is framed as the comic’s protagonist. Would you consider Ozymandias and Rorscach to be character foils?

MA: It’s totally fair to say this. On the surface, they can’t be more different. When I envision Ozymandias I see the pristine marble of his great hall and when I see Rorschach, it’s him living in the squalor of a rundown apartment building where he is behind on the rent. Ozymandias is well-put together, buttoned up, and even has his own cologne, while Rorschach smells and doesn’t care much for his personal hygiene. But with all that said, they’re really not all that different. Each character looks down upon society and each feels that the way he sees things is best. Without revealing too much about the story, both are willing to go to great lengths and spare no costs (financial, moral, or otherwise) to achieve this understanding. And sadly, as a result, each character is in many ways completely alone; these thoughts isolate them from the outside world.

JW: One of the most interesting interactions in the whole comic for me is the confrontation between Dr. Manhattan and Rorschach at the end. It is so fascinating to see how despite Rorschach’s contrasting appearance with Ozymandias, the similarity they share is what saves one but kills the other. Even though Rorschach has a seemingly screwed-up moral code, his quest to deliver truth to the world was just and noble. Unfortunately, this desire for truth is a disturbance to the peace that Ozymandias achieves through his strictly immoral plan. This truly hammers home one of the larger beliefs of Moore and Gibbons, which is that the world is more complex than good and bad.

Typically this is where it would end: teacher teaches student, student learns and experiences something new – successful education! But that’s not the case here.

It just so happens that I have never read Jack’s all-time favorite book: Dune. So it is only fair that now that we’ve closed Watchmen and put it back on the shelf, we enter the desert planet Arrakis and discuss Frank Herbert’s Dune next!