The Secret Killer of Murderer’s Row

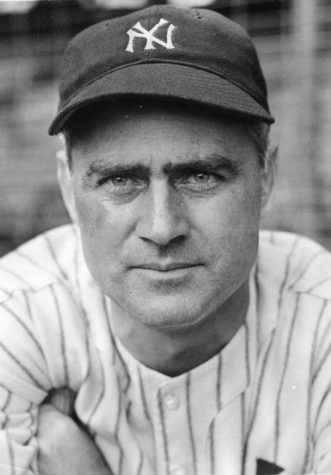

There have been eight men to both play for the Yankees for their entire career and be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Many of them are household names: Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, and Phil Rizzuto. The eighth man is far from a household name. And yet, he is still a crucial part of Yankees history.

There has been a ton of discourse about the utterly dominant Murderer’s Row New York Yankees of the 1920s. The 1927 and 1928 teams won back to back titles without losing a game in either World Series. The team was, of course, headlined by Babe Ruth and the aforementioned Lou Gehrig. They are not only two of the most recognizable names in baseball history, but also vital characters in this story.

A die hard Yankees fan might know that that team also employed Tony Lazzeri, a do it all utility infielder who batted behind Gehrig and was also inducted into the Hall of Fame. However, Lazzeri is not our mystery man: though he is a Hall of Famer, he spent the 1938 and 1939 seasons playing for the Cubs, Dodgers, and Giants.

Our eighth man is Earle Combs. He was many things: the leadoff hitter for that Murderer’s Row team, an MLB Hall of Famer, the “Kentucky Colonel,” a notable humble family man, Babe Ruth’s sidekick, and the antithesis of Lou Gehrig.

Combs was at Eastern Kentucky State Normal University (now Eastern Kentucky University) when his baseball career began. In a recreational game, the school’s baseball coach recognized his talent and insisted he join the school team. A few years after he graduated, he continued to pursue a career in baseball, signing with the Louisville Colonels of the American Association. His manager on this team was Joe McCarthy (no not that one). Combs’ Colonels tenure got off to a brutal start, as he committed two errors, one to lose the game, in his debut. McCarthy squashed the doubts Combs had of himself, telling the 22 year old “Look, if I didn’t think you belong in centerfield on this club, I wouldn’t put you there. And I’m going to keep you there.”

At the start of the 1924 season, his contract was purchased by the New York Yankees. His first season wasn’t anything remarkable, appearing in just 24 games. However, from 1925-35 Combs was the everyday center fielder in the Bronx. This, of course, includes the unfathomable 1927 Murderer’s Row squad. That year he led the league in hits with 231 and kicked off a four year stretch in which he led the majors in triple three times. Combs batted over .300 every year, except for two. From 1925 to 1932, Combs compiled 1,563 hits, the second most of anyone in that timeframe. He batted .350 with a .901 OPS in his three career World Series (1927, 1928, 1932), and ended up as a champion each year.

Combs’ Yankees tenure saw the end of one Hall of Fame manager’s time in pinstripes, and the beginning of another. Miller Huggins was the Yankees skipper from 1918 right up until his death in the midst of the 1929 season. All American League games were canceled on September 27, and when the Yankees returned to action the following day, Combs collected 4 knocks and 3 runs batted in.

It took the remainder of the 1929 and all of the 1930 season, but the Yankees found their replacement. Coming just one year removed from winning the NL pennant with the Cubs, it was Combs’ old friend, Joe McCarthy (still, not that one). McCarthy would serve as the manager for 16 seasons, winning an outstanding seven World Series.

Combs’ career was changed dramatically on July 24, 1934, as he was chasing a ball off the bat of Browns third basemen, Harlond Clift, in St. Louis, and ran into the outfield wall at top speed. He severely damaged his knees and shoulders, and worse of all fractured his skull. He spent 2 months in the hospital, and his life was in question for most of it. He managed to come back to the Yanks for 89 games in 1935, but that year concluded his 12 year career.

Combs was revered by both his teammates and the media for his everlasting humility and humbleness. Both of his Hall of Fame managers fell in love with the soft-spoken, non-problematic, and easy going center fielder. He broadcasted that sentiment for the entire baseball world in the summer of 1970, at his Hall of Fame induction ceremony. “I thought the Hall of Fame was for superstars, not just average players like me.”

Combs’ ability to get on base at the top of the order was part of what made those Yankees teams so deadly. Babe Ruth can hit all the home runs he wants, but he can’t guarantee that they’ll be driving in multiple runs. Combs’ ridiculously good OBP numbers supplied Ruth with the ability to be even more of a game changer.

Ruth had nothing but the utmost respect for Combs, saying that “Combs was more than a good ballplayer; he was always a first-class gentleman,” and constantly admiring his modest, sober, and biblical nature.

Between the friendship between Ruth and Combs as well as the absolutely mind-boggling numbers Murderer’s Row put on the board, it should come as no surprise that Combs and Ruth formed the best Batman and Robin duo in MLB history. Let me explain.

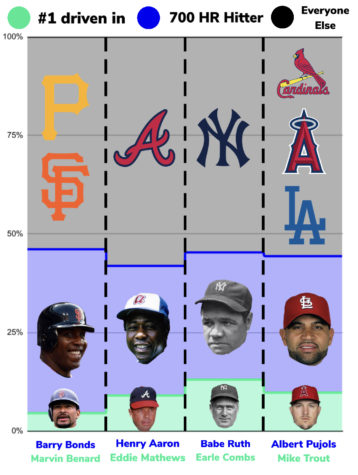

First of all, I don’t mean that they played the most together or that they were the most iconic together. Instead, what I mean is that Combs was the best ‘sidekick’ in baseball. Take a look at the graph below.

That graph displays the four people to hit 700 career home runs: Barry Bonds, Henry Aaron, Babe Ruth, and Albert Pujols. It maps out each of their career RBI totals. On the bottom, the mint color, is what percentage of career RBIs of that hitter belong to the teammate they drove in the most. The blue portion, in the middle, is how many times they drove themselves in, which obviously coincides with their home run total, and finally the black portion is everyone else that scored on an RBI from them.

The mint territory is actually filled with very notable players. Obviously it includes Combs, but it also houses Eddie Mathews, Mike Trout, and Marvin Benard. Mathews played over a decade with Henry Aaron on the Braves, hit 500 home runs, and is also in the Hall of Fame. Mike Trout has already won 3 MVP awards, and is one of the best players in baseball right now. Marvin Bernard. . . hit leadoff in front of Barry Bonds for several years, really his only notability in baseball history.

Despite that, Combs still towers over everyone in the mint section. He makes up 13.1% of Ruth’s RBIs, while Mathews and Trout take up roughly 9% each and Benard is at a measly 4.5%.

Just as Ruth was one of the most prominent home run hitters in the history of the game, Combs was more often driven in by the Sultan of Swat more than any other two teammates to play together. He was silently the best run scoring accomplice of all time.

Combs was a prototypical 1920s leadoff hitter, he refused to strike out and had the speed to steal early and often. So much so that with the Louisville Colonels he earned the nickname ‘The Mail Carrier’. However, upon his arrival to the Yankees, Miller Huggins did not want him being thrown out and taking away precious at bats from Ruth, and Gehrig.

Huggins told him that, “Up here, we’ll call you the ‘Waiter,’” because he would just wait for Ruth and Gehrig to do the dirty work.

That didn’t stop Combs though, who still attempted to steal 168 bases during his tenure in the Bronx. Which isn’t a whole lot. The issue is that he was only safe in 98 of those instances, 58% of the time. An absolutely abysmal rate for a supposed electric runner.

One of these caught stealings took place on July 28, 1926. The Yankees were ahead 3-1 on the St. Louis Browns in the 9th inning. Combs stood on first base, having just singled in that third insurance run. Mark Koenig hit a ball softly right back at the pitcher, Ernie Wingard. Up stepped Lou Gehrig. Gehrig was 2 for 4 on the day, with a double and a run scored. Despite this, Combs took off for second and got gunned down by catcher Wally Schang. He was thrown out, and Gehrig ended the game with the bat in his hands.

This was not an isolated incident. Over the course of their overlapping Yankees careers, Combs robbed Gehrig of an at bat with a caught stealing eight times.

- June 27, 1925

- July 28, 1926

- August 9, 1928

- September 12, 1928

- May 12, 1930

- June 10, 1930

- July 11, 1932

- May 7, 1933

Now, this might seem insignificant, and in normal cases this might be. Lou Gehrig’s career was cut tragically short due to his diagnosis of ALS disease. At age 36, with plenty of pop left in his bat, he retired and had to step away from baseball. He finished his career just short of one of the most notable milestones in baseball of 500 home runs.

Gehrig’s last home run put him at 493, which is the closest to the mark without crossing the heralded threshold. Now, there’s no way to know for sure, but there’s a possibility that had Gehrig been given another, say seven or eight at bats, he would have achieved the milestone before succumbing to his disease. Which is, coincidentally, the exact amount of at bats Earle Combs robbed of him.

Now you know the story of Earle Combs. A formidable component in that elite Yankees squad of the late 1920s, Babe Ruth’s partner in crime on the base paths, and quite possibly the reason Lou Gehrig is not a part of the 500 Home Run Club. Combs was a true ballplayer though, and he was loved by all that surrounded him as he earned his way to the Hall of Fame.

Note:

Data from Baseball Reference

Stories and Quotes from National Baseball Hall of Fame and Society of American Baseball Research

James Nolan is a Senior at East Islip High School with an affinity for sports. His favorite sports are baseball, volleyball, and football. He’s been...